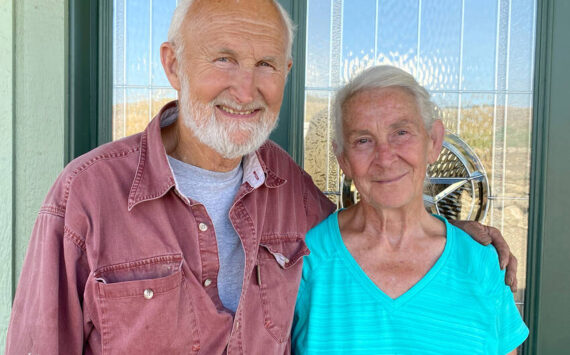

I’m going to tell you a secret about Lorraine Wiswell Grant, 87, a secret she kept from nearly everyone — including her husband and me, her son — until she died in Tifton, Georgia, on Friday, July 25, 2014.

Lorraine was very private, a trait that served her well as the longtime bookkeeper and credit manager for Lee Frank’s Inc. in Tonasket, Wash. She never talked about people who were late paying bills. She never talked about people the police were investigating, even to her son the investigative reporter. That was “none of your G-D business,” as she sometimes told me.

Now that she has passed away, however, it does seem our business to understand a little of the roots of her secrecy. In the Internet age, people surrender their privacy every day. Old age forced Lorraine to surrender it, too, when she could no longer see to read her own emails or clean up after herself. However, privacy still defined her. It gave her strength. The gravel would come in her voice and she’d say, “None of your business,” even as she lay in a bed unable to walk. As long as she controlled information, she was safe. People can’t hurt you with things they don’t know.

Lorraine’s secrets began at birth. She was born in Blairmore, Alberta, Canada, on Oct. 3, 1926, to Marguerite Bernadine Wiswell. No father is listed on the birth certificate. In those days people tried not to talk of such things. Lorraine was sent to be raised by her grandmother and uncle in Deary, Idaho.

Marguerite remained in Blairmore, became a well-loved school teacher, married and died trying to have a second child. Lorraine was only six, and barely knew her mother, though she would revere her all her life. Lorraine’s name wasn’t mentioned in Marguerite’s obituary. That was one of the things that hurt her all her life.

Byron Wiswell, her uncle, became Lorraine’s surrogate father. He was a big, kind, hard working man who farmed, logged and built homes. She rode horses and walked miles to school. Byron took her from the farm in Deary and moved to Moscow, Idaho, where Lorraine graduated from high school in 1944.

She attended the University of Idaho for a year, but was forced to drop out for financial reasons. She was poor but practical. She then attended Kinman Business College in Spokane, where she trained to become a bookkeeper.

After graduating, she moved to Tonasket, where she eventually landed a job at Lee Frank’s, the oldest general store in Okanogan County. Lee Frank gave her the most important thing in her life — respect. What mattered to Lee Frank was not the past but the present. What mattered was that she that she treated people fairly and honestly, and took care of the business. She did for more than 50 years.

She met Joseph Charles Grant and they eloped to be married in Dayton, Wash., in 1950. They bought a house on the hill in Tonasket, Wash. I was born, Thomas Arthur Grant, in 1953, their only child.

Her best friends seemed to be the women on her bowling team — Elenore Rampley, Gay Utzinger, Grace Yount and Pauline Sarff. Joe went on fishing trips and they went on bowling trips. She loved the practical jokes they played on each other — hopping out of the car at red lights and running around it, or painting pink all the walnuts on Utzinger’s tree.

Lorraine loved to travel. In her lifetime, she traveled all across the United States, Canada and Mexico. She would visit the home of her ancestors in Wiswell, England, and Kennebunkport, Maine. The fact that some of those ancestors fought at Lexington was a point of pride. She traveled to American cemeteries in France and battle sites on Midway Island. She wanted to travel to Ireland next, were she able.

When I was young, every time we drove on vacation, Lorraine would make an extra stop or two, pulling up in some dusty driveway with barking dogs, walking to the door and having a quiet conversation with the people inside. I would later figure out that the side trips were her way of privately asking people to pay their bills. She could be gruff, and straightforward, but she tried to give people every chance to take care of their debts without stirring up a fuss. She knew all the people who had credit at Lee Franks, and they mattered to her. If she wanted people to pay, she had to keep lines of communication open.

One time, while Lorraine was away, a clerk at the store sold a gun, ammo, and a bag of groceries — on credit — to a woman who lived in the hills near Tonasket. Lorraine knew the woman was having trouble with her husband, immediately got in her car and drove to the isolated home. The woman was sitting on her porch with the rifle on her lap, drinking from a fifth of whiskey. She told Lorraine that when her husband got back home, she was gong to shoot him. Lorraine convinced her to give back the rifle — no charge, and she could keep the groceries — and to move to a women’s shelter.

She worked six days a week at Lee Frank’s until she was nearly 80, climbing the stairs to her office on replacement knees and hips. For years, Lorraine served on a juvenile diversion board, trying to help young people in trouble find a better path. She heard many stories. And she kept them to herself. But tough as she was, her emotions ran close to the surface. I remember when she learned that her granddaughter, Grace, had been given the middle name of Marguerite. Lorraine cried in soft little gasps, trying to hide her tearful joy. Perhaps that was small proof of the family she’d created. I would never have discovered Lorraine’s deepest secret until I finally opened her records, if it hadn’t been for her lapse in memory a few years back. She hid her passport in the spaghetti drawer one time when she traveled to visit us in Georgia. She forgot where it was. We had to get her a new passport, because these days you can’t even drive to Canada for dinner without a proper ID. As I was helping her with her computer, I saw her Certificate of Citizenship. Because she was born in Canada to an American mother, at age 19 she obtained this special document to prove her national allegiance.

Her photograph is there, young with dark hair. And her real name is printed: “Yvonne Lorraine Wiswell.”

Yvonne? “Mom, who is this Yvonne?” I asked. “None of your G-D business,” she said.

Lorraine — no one ever knew her as anything else — had decided long, long ago, perhaps when she was only a child, that she’d be Lorraine. No other document lists her as Yvonne — not her driver’s license or marriage license or passport. And I don’t see anything wrong with that. She created herself in her own image, not the one that people once tried to cover up.

She flew as Lorraine Grant to visit Tifton, Ga., in October, fully intending to return home to Tonasket in the spring. However, a blood clot in her leg, a badly infected gall bladder that had to be removed, and, ultimately, a failing heart prevented her from getting around very much. She made it through the winter, seeming to gain strength every day. Her great friend Terry Mills flew from Tonasket to spend two weeks with Lorraine in the spring, helping to restore her good humor and love of life.

On the day before she died, we took her out to lunch at Ruby Tuesday’s. It was the first time in eight months that we had been able to take her to a restaurant. The waitress arrived and asked what we’d like to drink, and Lorraine immediately replied, “I’ll have a margarita.” She ate salmon and mashed potatoes and shrimp. We laughed and joked. We were happy. The next day, she was gone.

So here’s to Lorraine, or Yvonne, or whomever: You’re more than a name or a lineage. You’re the person who made her own way in the world, creating an identity as someone people around you could always trust. You kept secrets because you didn’t want anyone hurt by supposition and stereotypes. You defined yourself by your actions, and all the things you did that make the world a little better for people around you. I was certainly the beneficiary of that, but I suspect many others were, too.

Lorraine said that when she died she wanted people to have a party, and enjoy a good time. That party for Lorraine Wiswell Grant will be held on Wednesday, Aug. 6, at the home of Jerry and Terry Mills, 233 E. 2nd St., Tonasket, Wash. The social hour starts at 5 p.m. and dinner will begin at 6 p.m. Following dinner, everyone will have a chance to say a few words to remember her, if they choose.

She is survived by her son, Thomas, of Tifton, Ga., and his wife, Mary Ann; two grandsons, Sean Connery of Portland, Ore., and his wife, Stacey, and Patrick Connery of Minneapolis, Minn.; and three great grandchildren, Grace Connery, Ireland Connery and Eli Connery. She was preceded in death by her husband, Joseph, and her grandson, Thomas Connery, both in 1991.

In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to the Tonasket Community Scholarship Fund at Tonasket High School c/o US Bank, P.O. Box 508, Tonasket, WA 98855.

Comments are closed.