Ownership of powerhouse offered by Okanogan County PUD

Submitted by Chris Moore, Executive Director

Washington Trust for Historic Preservation

CHELAN – The Washington Trust for Historic Preservation announced its annual list of Most Endangered Historic Properties in the State of Washington on Monday, April 25. The announcement came during the organization’s This Place Matters reception, held at the Lake Chelan Chamber of Commerce. The reception is an affinity event hosted by the Washington Trust to kickoff this week’s RevitalizeWA conference in Chelan.

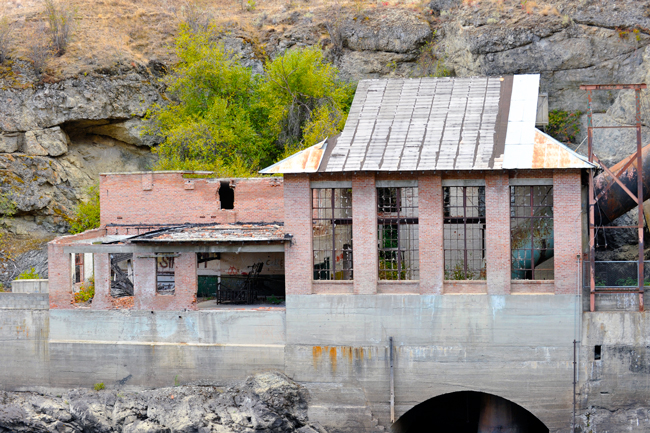

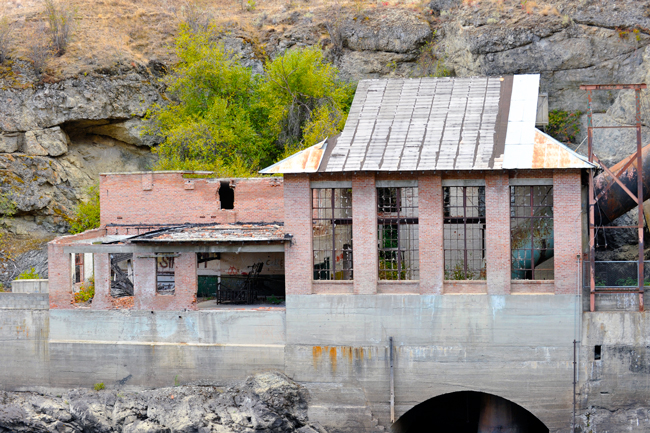

The gold rush spurred early pioneer settlement of the Okanogan River Basin, but after 1914 the area increasingly turned to agriculture given the railroad’s ability to provide efficient and reliable transportation of goods. The Enloe Powerhouse and Dam on the Similkameen River were built in 1922 to meet the electricity demands of the local mining industry and an increasing population in and around Oroville, Wash. With the improved infrastructure, the new dam in turn greatly contributed to the extensive growth of the Okanogan Valley. The dam and powerhouse operated until 1958, at which point the Bonneville Power Administration transmission lines reached the area, providing electricity from the Columbia River.

A new powerhouse is proposed for the area, prompting the Okanogan County Public Utility District to release a solicitation seeking a party interested in taking over ownership of the Enloe Dam Powerhouse. Qualified applicants need to “demonstrate capacity and capability to adapt and utilize the facility for recreational, historical, and/or community use,” with an emphasis on historical given the powerhouse’s listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

While the powerhouse is remote and in disrepair, it does afford a unique opportunity to tap into tourism and recreational activities for which the Okanogan Valley is known, including fishing, hiking, wine tasting, and visitation to other historic sites nearby. The property poses an adaptive use challenge, but local supporters are hopeful the powerhouse can be restored for community and tourism use given the building’s connection to regional history and development.

The remaining historic properties being named to the 2016 Most Endangered List are described as follows:

Local businessman Clint Dobson is credited with building the unique collection of structures known as the LaCrosse Rock Houses and Station between 1934 and 1936. Encompassing three houses, three cabins, and a service station, all buildings prominently feature basalt stones collected from the surrounding fields. Dobson was not a master stone mason – rather, basalt stone was the most readily available material in the area during the Great Depression.

Local farm hands, workers, and railroad crews used the houses and cabins as rental units, while the station offered a service and repair shop. Although the structures have not been in use since the 1960s, all but one of the houses remain. Those left standing are in critical danger of collapse if they do not receive repairs to stabilize and secure the stone and structural elements.

Hopes for rehabilitation were lifted when a local family gifted the property to LaCrosse Community Pride, which enjoys a strong track record of successful community development projects in town. Following the closure of the town’s only grocery store, LaCrosse Community Pride embarked on an effort to re-invent that site as an ongoing enterprise and community center. Today, the building houses a new grocery store, along with the local library, a community meeting space, and two rentable office spaces. The group also organized efforts to return a bank to the town when the local branch closed: they purchased the bank building, secured a new tenant to run the bank, and are working on finding another tenant for the adjacent café.

With several successful revitalization projects under its belt, LaCrosse Community Pride is now turning their attention to the rock houses and station. They have worked closely with Washington State University’s Rural Communities Design Initiative, involving the community as plans for the buildings develop. A key goal of the community is to ensure that any the project captures the unique nature of the basalt buildings and highlights the importance of the resources to the people of LaCrosse.

Providence Heights College was founded in 1961 as a response to the Sister Formation Conference. Started in the 1950s, the Conference initiated an inter-congregational effort to enhance the professional lives of religious women. Activities of the associated “Sister Formation Movement” included promotion of college education for sisters. Providence Heights College was one of only two institutions in the nation established at that time specifically for this purpose.

The campus, located within the City of Issaquah on a 29-acre parcel atop the Sammamish Plateau, enjoys peek-a-boo views of mountains and city skylines. Noted regional architect John S. Maloney designed the college campus, continuing his status at the time as the go-to architect for the Seattle Archdiocese. The campus centerpiece is a striking chapel with steeply pitched gabled clerestory windows infilled with stained glass. Together, these features form a remarkable modernist interpretation of Gothic design elements. The windows were created by Gabriel Loire, a world-renown stained glass artist from France. In addition to the chapel, the campus complex included classrooms, administrative offices, recreational spaces, and living quarters associated with the college.

The National Register-eligible campus is significant as a representation of the Sister Formation Movement which had a profound role in changing the experience of Catholic women in the United States. It was built during a volatile period when the influence of American culture, a new emphasis on education, and the Second Vatican Council collided with the older, more traditional understanding of authority and obedience in the Church, significantly altering the face of Catholicism in this country.

A shift to integrate religious education with secular student populations coupled with declining numbers of women entering the religious community forced the college to close in 1969. The Sisters continued to operate a conference center in the facility before selling in the late 1970s to Lutheran Bible Institute, later known as Trinity Lutheran College. The present owner, City Church, purchased the complex in 2004. There is currently a memorandum of agreement for purchase of the property between City Church and a housing developer, who plans to scrape the site to make way for over 100 single family homes.

With development in Issaquah and Sammamish exploding in the last decade, supporters are eager to preserve this significant piece of the area’s history. The campus is in excellent condition and ideally could be used in its current configuration for any number of institutional purposes. At the very least, however, supporters would like to see potential new construction thoughtfully integrated with the key historic elements of the campus. A creative approach could retain the remarkable mid-century chapel and college buildings, resulting in a unique residential development reflecting the peaceful and reflective history of the site.

The site of the present-day Woodinville School has served as home to an educational facility since construction of the first wood-frame schoolhouse in 1892. This building later relocated to the back of the district-owned lot when a new school took its place in 1902. A subsequent fire prompted the construction of a brick, ‘fireproof’ school in 1909, leading to conversion of the original 1892 structure into teachers’ housing. Funding through the Works Progress Administration led to expansion of the brick structure in the 1930s, with a final remodel occurring in 1948 when architect Fred B. Stephen delivered on an effort to balance the façade. In its final iteration, the building is an example of “stripped classicism” that combines the symmetry and formality of Beaux-Arts classicism with the sparseness and controlled detailing drawn from European Modernism.

After nearly a century serving Woodinville students, the school district mothballed the school in the 1980s. Following incorporation, the newly formed City of Woodinville moved into the building, eventually purchasing the site from the district. When a new facility for City Hall was constructed on the property in 2001, the historic school closed once again. Local community members were hopeful at first that the city would rehabilitate the old school, but a decade of false starts has deflated those hopes.

Since 2005, the city has pursued public/private partnership opportunities for the rehabilitation of the school, conducting feasibility studies and issuing requests for proposals. Many in the community felt the most recent proposal to convert the property into a brewery and boutique hotel offered the best option to date, but it failed to gain the needed city council support. While the city continues to seek ideas for re-use, supporters fear “demolition by neglect” will soon make any rehabilitation project unrealistic.

In 1886, a British steel tycoon named Peter Kirk envisioned a “Pittsburgh of the West” to be established in the area he incorporated as Kirkland. Attempting to turn this vision into reality, the Kirkland Land and Improvement Company constructed eight homes in 1889. One of these eight, the Trueblood House, differs from the other residences: while seven of the homes were built for steel mill executives in the West of Market area, the Trueblood House sat East of Market and, based on newspaper records, was built for Doctor William Buchanan, Kirkland’s first physician. A second physician, Doctor Barclay Trueblood, took up residence in 1907 and today the house retains his namesake.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the Trueblood House is an excellent example of the wood-frame English Mill Town architecture that is present in Kirkland due to Peter Kirk’s influence. While Kirk’s plan to create a center of steel production never fully materialized, the area grew in population as other industries developed, including wool production and shipbuilding. By the mid-twentieth century, construction of bridges across Lake Washington made Kirkland a popular bedroom community for urban commuters to Seattle.

Kirkland remains a popular residential city, yet due to dramatic regional economic growth and an associated spike in land values, smaller, historic houses increasingly fall victim to the teardown trend. The current owners of the Trueblood House plan to build a new, larger residence on the property. Preferring to avoid demolition, the owners are willing to support relocation of the structure to a new site. The Trueblood House is one of very few early residential structures remaining able to represent the founding history of Kirkland.

The Dvorak Barn in Kent hearkens to the city’s early years when the area was home to a significant farming community. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Kent got its start raising potatoes, onions, and hops, expanding with lettuce, eggs, dairy, and poultry after the turn of the twentieth century.

The damming of the Green River in 1962 and the completion of Interstate 5 in 1966 played pivotal roles in transforming Kent from a farming community to the industrial center it is today. While farming activity remains present in the Kent Valley, many of the historic resources representing the area’s agricultural heritage have been lost.

The Dvorak Farmstead is one of these resources. Homesteaders established the farm along the banks of the Green River by erecting a farmhouse in 1906, while construction of the iconic barn, still recognizable today, came two decades later in 1925.

The City of Kent, in partnership with King County, is embarking on the Green River Levee Improvement Program, requiring construction of a levee directly through the Dvorak Farmstead site. Although the farmhouse and several outbuildings all need to be removed, the barn retains the most integrity and is identified as one of few remaining buildings symbolic of Kent’s agricultural roots. Saving the barn is a priority for local advocates, who hope to relocate the structure and find a new community use.

In 1946, the Washington State Department of Game, known today as the Department of Fish & Wildlife, acquired 160 acres of the Maplewood Springs Watershed in Puyallup. The goal: access to an abundant supply of clear spring water for the production of game fish.

The ensuing Puyallup Fish Hatchery complex, built in 1948, consists of a natural, gravity-fed water supply, various raceways, sixteen round ponds, an incubation building, a shop building, and residences for operators. The design of the main building is hybrid in nature as it takes cues from public structures built during the late 1930s and more modern, post-WWII-era construction methods and materials.

The facility continues to remain in active use as a trout hatchery, but is slated to be converted for salmon production. The conversion requires that certain alterations be made, and local advocates are concerned the National Register listed complex will be adversely impacted by the changes. The hatchery remains important to Puyallup and the region not only for fish production, but also because of the open access for visitors, as a venue for local events, and as an educational opportunity for area students to learn about the history and role of hatcheries throughout the state. For these reasons, the project offers a unique adaptive re-use opportunity, as the facility overall needs substantial repair and efficiency upgrades.

The Department of Fish & Wildlife has expressed optimism that a thoughtful rehabilitation will result in an updated facility that retains its historic character while meeting agency needs for salmon production. Agency officials understand the educational and historic importance of the hatchery and are engaging with the community and other concerned parties in order to ensure positive outcomes for the historic complex.

Since 1992, the independent, nonprofit Washington Trust for Historic Preservation has used its Most Endangered Historic Properties List to bring attention to over 140 threatened sites nominated by concerned citizens and organizations across the state. The Washington Trust assists advocates for these resources in developing strategies aimed at removing these threats, taking advantage of opportunities where they exist, and finding positive preservation solutions for listed resources.