Oroville’s Dorothy Scott Airport named for World War II aviator

No stone angels, no blocks of marble with massive shoulders pointed the way to her grave. But the three small American flags fluttering in the breeze were hard to miss in the vast grassy expanse dotted with flat stones. A rectangular slab identified her: Dorothy Faeth Scott; Oroville, Washington, February 16, 1920 – December 3, 1943, plus the letters W.A.S.P., a winged star within a circle, and a pair of pilot’s wings. The bronze flag holder bears the inscription “Dorothy Scott WAFS Pilot – US.”

Women pilots — 1,102 of them — flew military aircraft for the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) in World War II. They were known first as WAFS (Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron) and later as WASP — Women Airforce Service Pilots. Thirty-eight died serving their country.

Dorothy Scott was one of the thirty-eight.

Dorothy is buried in Valhalla Memorial Gardens in Burbank, CA. Her mother, Katherine Faeth Scott (1882-1946), is buried next to her. In 1954, Dorothy’s father, G.M. Scott, joined his wife, his daughter, and his father in the family plot.

On September 10, 2009, I stood looking down at Dorothy’s final resting place. What did I really know of this young woman—of her unselfish patriotism? Does that simple flat stone do justice to what she gave for her country—her life, at age twenty-three? What can do justice to such a sacrifice?

Dorothy’s story was almost lost to us.

If not for her twin brother Ed’s love and devotion, we would know next to nothing about the 25th woman to join that first squadron of World War II women fliers. But Edward Scott — who many of you remember — saved his beloved sister’s wartime letters home and donated them to the WASP Archives in 2000, not long before his own death.

I’m a lifelong writer, career journalist, and now an author. I first encountered this remarkable young woman, Dorothy Scott, when I began researching the WAFS. Nancy Love was their leader. She was recruiting experienced women pilots to ferry the Army’s small trainer aircraft to the newly established flight training schools in Texas and elsewhere in the South. It was fall 1942 and the war was but a few months old

In the 12 months she flew for Nancy Love, Dorothy proved to be one of the most versatile of the women pilots. Her letters home vividly describe her flying adventures, like this one flying dual in a two-seat basic trainer aircraft with a male officer.

Dorothy Scott was one of the thirty-eight.

Dorothy is buried in Valhalla Memorial Gardens in Burbank, Calif. Her mother, Katherine Faeth Scott (1882-1946), is buried next to her. In 1954, Dorothy’s father, G.M. Scott, joined his wife, his daughter, and his father in the family plot.

On September 10, 2009, I stood looking down at Dorothy’s final resting place. What did I really know of this young woman—of her unselfish patriotism? Does that simple flat stone do justice to what she gave for her country—her life, at age twenty-three? What can do justice to such a sacrifice?

Dorothy’s story was almost lost to us.

If not for her twin brother Ed’s love and devotion, we would know next to nothing about the 25th woman to join that first squadron of World War II women fliers. But Edward Scott — who many of you remember — saved his beloved sister’s wartime letters home and donated them to the WASP Archives in 2000, not long before his own death.

I’m a lifelong writer, career journalist, and now an author. I first encountered this remarkable young woman, Dorothy Scott, when I began researching the WAFS. Nancy Love was their leader. She was recruiting experienced women pilots to ferry the Army’s small trainer aircraft to the newly established flight training schools in Texas and elsewhere in the South. It was fall 1942 and the war was but a few months old

In the 12 months she flew for Nancy Love, Dorothy proved to be one of the most versatile of the women pilots. Her letters home vividly describe her flying adventures, like this one flying dual in a two-seat basic trainer aircraft with a male officer.

“We made a formation take off between smudge pots lining the runways. It was night! Oh pop, I’ll never in all my life forget that ride! There we were nearly touching the next plane and guided only by small lights and the flare of the exhaust.

We cruised in close formation for quite a ways, then we separated some. All of a sudden — swish, and we were in a snap roll! From there to Memphis I had trouble telling when we were right side up and when we weren’t. Loops, slow rolls, Immelmans. I’ve never had such a ride.

It was a very clear night but dark so the stars above looked a lot like the small clearing fires below and I had to check the instruments to believe anything.

We approached Memphis, and that was a sight! From afar it looked like a patch rug painted with luminous paint, and as we drew near it got brighter and more definite. We came right over it at 6,000 feet and spiraled down. All too soon we landed and shocked the natives by walking into the Terminal with flying suits on and a couple of handsome officers. They stayed with us ’til plane time.”

Dorothy and another WAFS had delivered two basic trainers to a remote air field in Arkansas. Two male pilots offered to fly them to Memphis to catch an airliner back to base in Dallas, rather than the young women having to ride a bus all the way to the Memphis airport.

Dorothy moved quickly up the transition ladder, flying increasingly larger, faster, more complex aircraft. She proved to be so proficient, in November 1943 Nancy Love named her to the first class of pilots — male and female — to attend pursuit training. Flying pursuit aircraft — the WWII fighter planes — was a coveted assignment.

Dorothy was on her way to Palm Springs, California, to learn to fly the Army Air Forces’ best — the P-51 Mustang (her personal dream plane) as well as the other single-engine fighter aircraft in the AAF’s arsenal.

In pursuit of that dream, she died in a senseless training accident on December 3. All that promise, all that drive, all that passion gone in an instant.

Oroville, her family, her friends, her country — the future — lost someone special that day. We’ll never know what great things Dorothy might have done with her life. Her college English paper that earned her an A-Plus gives us a glimpse of the vision she had for the future. It is the Epilogue to my book that tells her story.

Ed knew how special she was. “Somehow, my father realized that his sister was different,” Tracy told me. “I think he regarded her as the smartest woman who ever lived.” DeVon, the editor of the newspaper, told me that Ed used to come by the newspaper office and talk to him about Dorothy. “He didn’t want her to be forgotten.”

When I read her funny, descriptive, yet deeply personal letters, I knew I had to write her story.

In 2005, I came here to Oroville to begin my search. At the Gazette-Tribune office, Gary DeVon brought out the bound volumes from Dorothy’s years. I found articles on her and the family. I read that her father, G.M., built the Oroville Airport. And I read that, on January 17, 1944, it was renamed the Dorothy Scott Municipal Airport “in honor and memory of Dorothy Scott, who freely offered her services to her Country and who gave her life in the Service.”

Before I left, I visited City Hall and the town clerk’s office gave me Ed and Ethel Scott’s address in California. Eventually, that led me to their son, Tracy Scott. Ed had passed away in 2002.

Tracy and I met in 2009. That is when the book that would tell Dorothy’s story began to take shape. His help — sharing the family archives and photos — was the missing piece I needed. Now the book had life. All I had to do was write it.

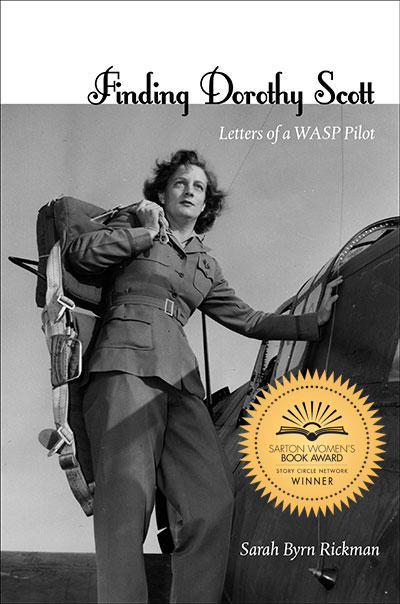

Texas Tech University Press published Finding Dorothy Scott: Letters of a WASP Pilot in fall of 2016.

I like to think Dorothy is up there smiling — better yet, laughing, fun-loving person that she was.

Thank you Oroville for remembering her.