Part I: A local mystery solved

Editor’s Note: Local historian Karen Beaudette wrote a three part series looking into the mystery of the man named Charles E. Long who ended up buried in Loomis after being “Shot by the Okanogan Kid.”

We serialized the article every other week and have joined them into one article here. Please let us know whether you’d like to have more historical articles from Beaudette in the future, as she says she would be happy to do so, although perhaps not as long, as she refers to the story of Charley Long and The Okanogan Kid as the ‘story of a lifetime.”

G.A.D.

© Copyright 2015 Karen Beaudette

LOOMIS – The tombstone arrived at the gravesite in Loomis 110 years after the occupant made the trip. There may have been a time when the small society of the old mining camp knew well just who and what Charles E. Long was in 1894. In 2004, the chiseled name was only a mystery. His eternal resting place in the Mountain View Cemetery had been long-ago forgotten, the original marker destroyed in an earlier wildfire. No record of this internment existed. Maybe there had been some kind of mistake.

Even more puzzling than where, exactly, to put the rectangular slab of granite was the epitaph. Regular visiting mourners might suppose that the stone missed its intended destination by many miles or many misunderstandings: “OREGON PIONEER” implies a well-known early settler of respectability and a tendency to roam. “SHOT BY THE OKANOGAN KID,” on the other hand, contains a contradictory hint that the deceased was perhaps someone who could have been, should have been shot. Perhaps Charles E. Long most likely belonged in a Boot Hill, a common name in frontier towns for burial grounds of those who died violently – with their boots on. The stone tells a life story that fits none of the then-known facts of Loomis in 1894. Outsiders, yes; plenty of them around, looking to strike it rich. Shootings not exceptional–

at least one took place outside the saloon, if old-timers’ stories had it right. Long was mentioned decades afterward in fuzzy reminiscence of the shooting; however, there exists not a single mention in local lore of The Okanogan Kid or anyone who could have been The Kid: Not a lawman, gunslinger, outlaw, cowboy, rancher, or drifter.

Still, the tombstone wasn’t lost, it wasn’t even unexpected. Charley Long’s foster family in Oregon had tracked down his grave through old family records and the help of the cemetery caretakers in Loomis. A fourth-generation descendent of that family, David McNett, wanted to recognize one of theirs who, at exactly the same age, grew up in the same household as his great-great grandfather. Following his death, McNett’s widow forwarded the marker in a plain, brown wrapper—an ordinary cardboard box with peanut packing—along with the marvelous story of Charley’s past. “OREGON PIONEER” is a true description; but his life seems to have earned Charley Long the reputation of “OREGON DESPERADO.”

Charley Long was fondly remembered in the Howard family as the small boy who had been orphaned on the Oregon Trail and rescued by a famous frontier scout named Benjamin Allen. Allen took Charley and his brother, William Henry, to his in-laws in Eugene, Oregon. The date was sometime prior to the filing of guardianship papers in 1855 in Eugene, giving custody of the boys and their inheritance, one cow, to James Howard. Five years later, Charley Long, age nine, is registered on the 1860 U.S. Federal Census as being part of the Howard household (William Henry was apparently taken in by a different family as he is not listed on this census with the Howards). It is known that James Howard discovered gold near Prineville, Ore. in 1871 which became the famous Scissors Mine. Charley seems to have left the Howards and set off on his own.

Of Long’s whereabouts after the family relocated, McNett claims that Charley Long was a hired gun for the notorious McCarty clan—the family of Billy the Kid aka William Bonney also known by his real name of Patrick Henry McCarty–in Oregon Territory. He also mentions as documented fact that Long was known as an accomplice of Butch Cassidy, Harry Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid) and the Wild Bunch while they robbed trains and banks, creating havoc throughout Wyoming Territory. This seems a more romantic legend than probable reality since Charley was long dead by the heyday of the Bunch from 1894 to, say, 1908. Nonetheless, Charley was supposedly never captured or arrested for any of these outlaw activities attributed to him (others observed later that Long was something of a braggart). According to McNett’s long-postponed family eulogy, “Charley’s personal life was chaotic. Always on the run, he lived in many different places. Curiously, something in his careful upbringing remained with him all of his life and he returned periodically to [attend church services] with the family…despite his notorious reputation, he was loved by the family to the very end.”

Charley is also remembered in the Oregon history books, perhaps not so fondly, but certainly with a keenness for the often-repeated Old West tale of the shoot-out in the Prineville saloon in late 1893. Jon Skovlin [1996] wrote of consolidating at least “eight accounts of the [December 1881 shoot-out] as reported in newspapers or by eyewitnesses…” which took place in The Silver Dollar Saloon. Russell Blankenship’s account in his 1942 book And There Were Men centers around Hank Vaughan, the most colorful outlaw of Umatilla County. In fact, Vaughn is the focal point of almost all the published recollections of the event. Blankenship wrote that “Vaughan heard that a fellow named Charley Long had established himself as the champion bad man of the lower Deschutes regions of Central Oregon…” and he headed for Prineville to “make a personal investigation…,” finding his quarry at the Longhorn Saloon. Gale Ontko, author of the Thunder Over The Ochoco series on Central Oregon history, claims that Hank Vaughan “…challenged Charley Long to a shoot-out in the Bucket of Blood Saloon [in Prineville].” Further on, Ontko says the two men met at the Silver Dollar where “Vaughan was leaning on the bar sipping a beer when Charley Long—a reckless 37-year-old gunslinger—walked in” [this time in January 1882]. Long apparently fired without provocation and “calmly walked out and disappeared down the street.”

There may have been two encounters involving gunfire, in fact. Details, like the exact saloon location, from one episode seem to have drifted to the final outcome, including approximate dates, as the story is passed from ear to ear. Let’s stick with this version, taken from Ontko in And The Juniper Trees Bore Fruit where he relates the eyewitness account of James Blakely as printed in the Ochoco Review of 1882:

At the saloon showdown, Vaughan was reported to say, ‘Charley, let’s settle things right now.’ Then both men walked to the middle of the saloon and commenced shooting, Vaughan with a .44 Bulldog Colt and Long with a .38 five-shot Smith & Wesson. Ten shots were fired from close range. Perhaps faster on the draw, Long was reported to have fired first, the bullet hitting Vaughan in the forehead. Long’s second shot got Vaughan in the left breast over the heart but he still didn’t go down. Vaughan then fired five shots, hitting Long three times in the left shoulder. By the time the smoke had cleared, Long was laid out on a poker table to die. Vaughan stumbled out to the street and asked to be taken to the Longhorn Saloon where the doctor removed the bullet from above Hank’s heart. A later testimony by a Dr. Belknap reported that he couldn’t remove one of the bullets from Charley which lodged deep in his body. Neither man was expected to live that night. Despite being reported as dead, both recovered to live another day. Charley’s wounds in the shoulder ruined his left arm. Now packing a .41 caliber Remington derringer in a shoulder sling, his injury was apparently no handicap to his next role: Hired gun.

Nor did it keep Charley out of the Bucket of Blood. Reports at the time noted Long in conversation there with Col. William “Bud” Thompson, organizer of the Vigilante Committee to eliminate the criminals—mostly rustlers–of Wasco County. In Thompson’s own words, events of March 1882 prompted him to action: “I did not…tell the Deputy of my plans. I went to four men—men of unquestioned courage and discretion—and told them of my plans. These men [included] Charley Long.” The vigilantes’ presumed guilty parties managed to escape in the darkness of night. Armed with shotguns, Thompson and Long managed to round up their ten accomplices without a shot and haul them back to Prineville. By January of 1883, the Vigilance Committee was better organized and Charley was back on his feet. However, because he had not fulfilled his contract with the livestock association—which was to carry out committee instructions to rid the county of unwanted predators of the two-legged kind—Charley Long was replaced as a bounty hunter and wasn’t paid for his services. Rumor added that he lit out for Washington Territory.

The old-timers in the Oregon cow camps say that Hank Vaughan and Charley Long met one last time in Pendleton in 1893. When he heard Vaughan had been seriously shot up in another dispute, Long visited him on his deathbed, bringing flowers. Some even insist that he even joined Hank on the bed to offer condolences, possibly good-byes.

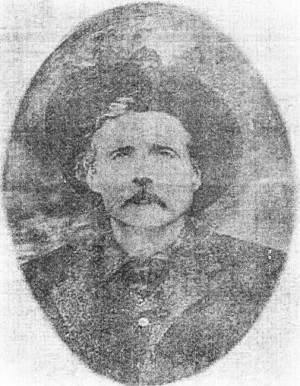

During the intervening nine years, there is no mention of Charley Long until he arrives in Loomis, Washington Territory around 1891 or so. Kathleen Grant Prince has described as being “tall, slender, quiet-spoken Virginian…with a soft Southern drawl,” according to her mother Susie Fruit Grant. Charley’s accent was more probably a Missouri drawl, learned in the Howard family as a toddler of age two or three. Readers who remember the actor Alan Ladd may notice that Charley does appear to closely resemble the hero of “Shane” movie fame. Prince goes on to state that family lore claims Long was feeling lonely while his hosts, the Guy Fruits, were away and decided to become acquainted with another bachelor in the area for company. She also hints that Charley’s reputation preceded him, causing a great deal of gossip in the sparsely-settled community.

Charley’s tombstone marks an unknown occupant’s gravesite in the Mountain View Cemetery, where the oldest identified graves date to 1894. The marker recognizes the storied past of the Boot Hill of the Old West and an Oregon desperado. We do know the circumstances of this violent death through the astonishing preservation of a 125-year-old Victorian-era scrapbook compiled by Mrs. Alan Palmer from the newspaper clippings she carefully pasted in an old government publication [now safely at the Okanogan County Historical Society]. From the original account from the short-lived Loomiston Journal of 1894, we even know the killer’s real name. Is he the Okanogan Kid?

Part II: A Desperate Fight at Palmer Lake

If you have read this far, you may recognize the photocopy of the original 1894 newspaper article printed by the Loomiston Journal in the January 4th issue, saved for all these years in Mrs. Alan Palmer’s scrapbook. At this point, the local press’s report of Smith’s confession to killing Charley Long is almost mysterious as the tombstone epitaph. This writers’ condensed version below will be an effort to sort out second-hand, even third-hand, hearsay and confusion in a coherent sequence. Editing out a lot of “he said” of the original article, the basic statements are as they were told to us by the Journal.

Lou Burrell told the hastily organized coroner’s jury on January 4th the story that Smith told to him: Smith said he was in the house alone , the dog barked, and he saw Charlie Long coming to the house He asked Long to come in and sit down but Long refused and asked for Smith’s father and for [Michael] Kelly. He was told they were “up to Phillip’s ranch”. Long then said, “I came to kill you”; Smith replied “You have, have you” and he fired at Long. Smith’s revolver went off twice but the chambers stuck and would not work. Long fired one shot, which did not hit Smith. The desperate fight of the newspaper headline followed the alleged gunplay as Smith continued his story: Smith grappled with Long after “he could not shoot anymore” and the two men got outside, Smith “striking and fighting” Long. As they struggled, Smith noticed a bullet wound in Long. After getting outside, Long said “Let me go home” and then fell down. Smith was afraid Long would “rally and shoot him” so he hit Long on the head with a double-bit ax. Seeing that Long was dead, Smith went to get a horse from the pasture and rode away. Smith said he took the gun that was Long’s to Conconully. [Later in the article we learn that Smith gave himself up to the Sheriff and was in custody on the day of the hearing, probably in Conconully.]

Witnesses testifying before the coroner’s jury are skeptical about this version of what happened. Long’s friends said that they believed he had no gun with him when he went to Smith’s. Other witnesses said there was not much evidence of a scuffle to be seen, except some blood in the house. Witness Ballou further asserted that the ax was used near the woodpile where the body had been dragged as there was a considerable amount of blood at that spot.

Dr. F. S. Reynolds was called to testify about the “wounds upon the person of Long”, as the press put it: Two bullet wounds were found, “in each case where the bullet went in and where it came out.” The doctor said the shot to the lower part of the neck was almost certainly fatal. The other bullet entered about “two inches above the right nipple and passed out the right side and below”, not necessarily fatal but very severe. “The head and face were battered and cut, the skull pierced, both with a sharp, blunt instrument”, also pronounced “not necessarily fatal”.

The good doctor added that during the autopsy he had found a ball protruding under the deceased’s skin, below the line of the shoulders. After much speculation, the jury decided this foreign object had been lodged there for quite some time. Just in case, Coroner Nathan Reed preserved the ball. Later, while dressing the body for burial, another ball was found in Long. The full account from the Journal is here quoted in full: “A ball had been fired directly at the head. The pistol had raised on being discharged and the ball had struck the skull about an inch above the base and glanced down the spine to where it was found by the doctor. The ball had been battered by coming in contact with the bones and it still carries two short pieces of hair…The ball is a .41-caliber. The pistol that Smith said was Long’s and which he carried to Conconully with him is smaller than a .41 or .45 cal. But the size was not determined here. The coroner has preserved this bullet.”

Everyone in Loomis probably had an opinion about what happened. The jury of six Loomis men decrees that Yep, George H. Smith killed Charley Long. The reporter offers his own take: “Smith’s story as told to Burrell admits all the ghastly details, but he claims it was a desperate fight…It was…as far as Smith is concerned, for he probably kept it up as long as there was motion in the body. [Smith] claims Long would kill him, as he did not know Long had no gun.” The editor goes on: Long’s friends told the jury that they believe he was killed as the door opened—that Smith commenced to shoot…even if Long had a pistol, he was in a dying condition immediately. They think Long fell in the house where there was blood found on the floor, but all the witnesses at the inquest stated there was no evidence of a scuffle. There was, instead, evidences of the body having been dragged the entire distance from the house to the woodpile.

The story you have read is fourth-hand, after all—Smith to Burrell to a reporter to the writer. All the same, this is the place in any good mystery tale where the suspects are assembled, all the clues are exposed and the truth comes out. Accusations of motive are made. In our case—reader and writer, the killer confessed, the fear of Charley Long was undoubtedly real; perhaps not for the suspicious stated intent of Long but more for his reputation as a gunslinger. Panic ensued all right; but the details appear to be an attempt to conceal prior intent to murder. Well, New Age Sherlocks, what do you think? The dog did bark, remember?

The editor of the Journal concludes his story with some background for the Loomis readers: “…there had been for some time legal troubles between Long and his friends and Smith and his friends…men who know the ways of gun fighters say that Charley’s visit to the cabin and finding Smith alone would almost inevitably lead to a fight. Smith says it did and poor Charley is a corpse.”

A week after coroner’s hearing, the case of the State vs. George A. [sic] Smith for the killing of Charles Long at Palmer Lake came up for a hearing before Justice of the Peace Fifield a week later. Sheriff Rush and Deputy Sheriff Wallace told Smith’s story “as Smith told it to them.” A dozen witnesses were sworn in but only five had testified when the Judge granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss the case and rendered a verdict of justifiable homicide. The Journal points out that “Smith was practically discharged on his own evidence although he was not put upon the stand.” The news report then goes on: “As no one claimed the revolver which Smith said was Long’s, Sheriff Rush gave it to Smith and he now has it in his possession.”

Part III: The Okanogan Kid: aka George H. Smith

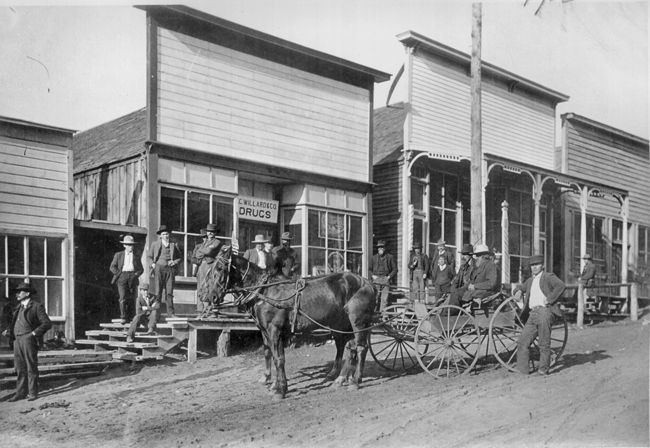

Okanogan County Historical Society photo #172

A name but not an identity–who might this confessed killer be? The long-gone tracks of historical documents that identify Smith are the reason you are reading this in 2015. George H. Smith–initial and all, to separate out the common George Smiths—turns out to be an elusive fellow. His father, up at Phillips’ ranch at the time, has been found to be George F. Smith, a cattle buyer out of Kittitas (Ellensburg). The same source also mentions meeting Junior Smith, a cook at the War Eagle mine, maybe a common confusion of George H. as a George F., Jr. The 1880 Federal census records the George F. Smith household in Kittitas Precinct [Yakima County] which includes one George, son, age 17, born in Maine [about 1863]. The same census lists T. Jefferson Smith with son Horris [Horace], age 8 and daughter Emily, age 11. 1850 Maine census records indicate Thomas Jefferson Smith is George F. Smith’s brother, in the same household as Coffin Smith, father.

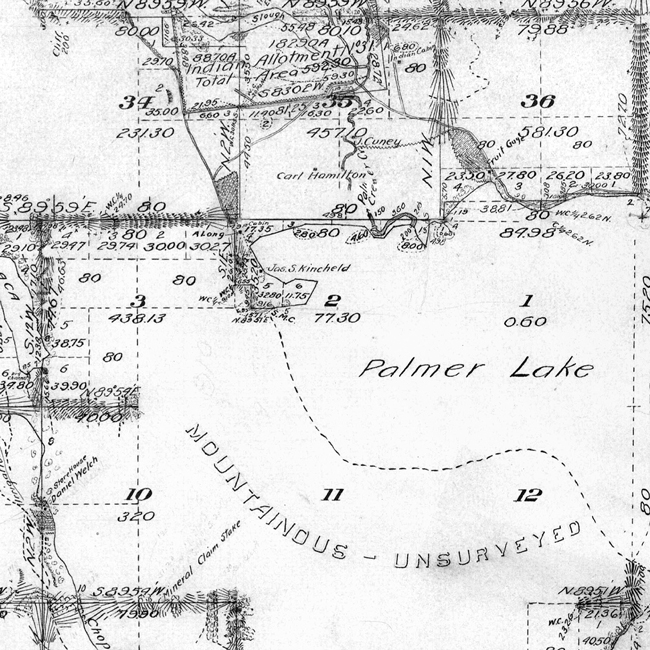

Significant to the Where? of Long’s demise, two Bills of Sale filed in 1889 at the Okanogan County courthouse, reveal that George F. Smith bought two ranches, one described only as “grantor’s [John Y. Phillips] ranch on the east side of Sinlahekin Creek” and one “commonly known as the John S. Palmer ranch situated at the foot of Palmers Lake lying between Hambletons and Bill Clauseys ranch and adjoining James Palmers ranch”. By the descriptions, it is impossible to determine which portion of the land contained the Smith residence, but the 1896 survey maps indicate the northwest corner of Palmer Lake [more about that later; it could later turn out to be “a clue”]. These sales took place seven years before the official U.S. Geological surveys, when land descriptions tended to include prominent rocks and trees but no map coordinates as they did not yet exist. Therefore, there was no legally binding “sale”, only a holding of place until the surveys were confirmed and the holder could file for homestead rights. Smith had a tenuous claim on this ranch land; worse, it required the continuous occupancy of a traveling man to legally hold it.

The Smith Brothers’ Cattle Company—George F. and Thomas Jefferson—are well known throughout eastern Washington, buying cattle in that cow empire around Walla Walla and Umatilla, Oregon. Any cowboy today would agree that if one buys a cow, one must move a cow to market, often a long trip and, if a large herd, with a large crew of skilled drovers. Leta May [Olmstead] Smith of Ellensburg (no relation) wrote that “Jeff Smith and his brother George were probably the best known and the best trail men in Kittitas. The Smiths were famous in the 1870’s and into the 1880’s on both sides of the Cascades for a cattle trail they had pioneered over Stampede Pass from the Kittitas Valley to the markets of Seattle (some of which they owned with wealthy partners). The winter of 1879-80 wiped out their extensive cattle herd, along with those of other big cattle ranchers of eastern Washington, and their Kittitas Valley holdings. Alas, they came to Palmer Lake just in time to see it happen again in the cow-killing winter of 1889-90 which took a heavy toll on Okanogan ranches; Smith lost 400 head in that winter.

The search for the Okanogan Kid, however, stalled right about here. Old Washington Territory census records taken in anticipation of statehood seem to indicate that Smith Junior lived on the coast between 1880 and 1900 in Seattle, alternately identified as “bookkeeper” or “clerk”. The atypical census information “born in Maine, [about] 1863” strongly suggest that these references are our boy. Even so, this is not information that would appear to support a theory about George H. being The Okanogan Kid. Even his father testified two years later that his son managed his nine meat markets in Seattle. Still, it’s difficult to imagine a cattleman’s son of that era as anything but a cowboy.

In January, 2015 the evidence turned up–in a Seattle Post-Intelligencer article of November 14, 1892, titled “Life on the Okanogan Range: A Cowboy Describes Interesting Sights and Scenes Among the Bunchgrass”. George H. Smith (the horses’ mouth, so to speak) describes eastern Washington climate and land as well as explaining that he spent the summer near Whitestone Lake with 5,000 head of cows on surrounding grazing land. [Aside: Quite a comeback in 2 years, from few cows after a bad winter to a huge herd]. He goes on to describe the cowboys “so romantic for their mysterious names” who are known only by their nicknames, such as Sorrel Horse Woods, Come Quick Kense, Henry the Kid. Smith makes it clear, without mentioning his own nickname, that he was most likely known in the cow camps of the territory as “The Okanogan Kid”.

The news of Charley’s Long’s killing got to Oregon in less than three weeks. The McNett family provided the obituary from the East Oregon Herald issue of January 31, 1894 of Harney County (location of Marcus Howard’s ranch). The obituary suggests that Charley Long, often in trouble during his early days, “…came out a pretty good man…at no time using a gun…he was quarrelsome when drinking but later years, at the advice of friends, stopped carrying a pistol and became a very quiet citizen.” Also mentioned was that Charley had left for Washington around 1892 and expecting trouble over a ranch.

While the Herald obituary clearly names George H. Smith as Long’s killer, that identity may have been typically better known as “The Okanogan Kid” in the cow camps of Oregon. It’s not too hard to imagine the news: “Who killed Charley Long (gasp of astonishment)?” “Don’t know his rightful name, only that he’s known around camp as The Okanogan Kid.” Later retelling of Charley’s death in the remote Okanogan country, picked up by Gale Onko and other writers eighty years later, may have had only the nickname to go by. Certainly “George H. Smith” is neither sufficiently romantic nor mysterious for chiseled granite through the ages.

BACK ON THE RANCH: Those keeping track of the Smiths have now counted up at least four. The newspaper has two Longs, Jack and Charley. The coroner’s jury has at least two names that figure in the events leading up to the confrontation at Palmer Lake, which will bring the tally up to eight. One of those events has George H. Smith’s name on it.

Our last installment will bring more facts to the table to unravel the tangled web presented so far. There’s a chance that readers will find a plausible motive, tucked in between the facts, that explains the stakes and the circumstances. For now, we have the classical moral of so many old Western movies: No matter what one becomes in life, a reputation as a gunslinger will surely take you to an early grave. And there remains the nagging mystery left behind in 1894: How many guns? Whose guns? Smith’s, Long’s? Self-defense? A shooting? Was this really a gunfight?

Part III: The Legend of the Monster of Palmer Lake

Charley Long met the Monster. Readers may recall that George H. Smith confessed to the jury that he was fearfully afraid of Long, causing him to defend himself with a gun and an axe. The State of Washington deemed Smith’s action as “justifiable homicide”. And the Loomiston Journal speculated that legal trouble between Smith and Long was the underlying motive. What we don’t know is whether Smith may have explained his fear of Long: Was it because of Charley’s reputation or because of some immediate circumstance? We don’t know what story Judge Firfield [sic] heard from the Sheriff that lead to his verdict to acquit Smith on justifiable grounds. But we do know about the legal troubles and we do know they were not between Smith and Long.

If you, Dear Reader, have been asking yourself why Charley Long was so far from his Oregon stomping grounds, the East Oregon Herald explains: “As Charley Long, once a resident of Heppner, had written about jumping a ranch [in Loomis, Wash.], stating that he expected trouble over the matter, Heppner people concluded…that he has had the trouble anticipated and once too often.” Additionally, the official records of Okanogan County have turned up the evidence of the legal trouble–most definitely about a ranch, which the bystanders of Loomis may have had only the vaguest gossip to go by.

A Quit Claim Deed was recorded by Okanogan County on October 10, 1892 (one of those dreaded historical dates) from William Case to George H. Smith that transferred a “piece and parcel of…the Case ranch…at the north end of Palmer Lake and bounded on the north by ranch of M. Kelley, on the east by the Palmer ranch, on the south of Palmer Lake, and on the west by Mount Chopacca, being 160 acres and…[much legalese here] one cabin.” This land was roughly adjacent to the ranch purchased by George H.’s father, George F. Smith, in 1889.

Charley Long certainly had a claim to “that certain ranche [sic] known as the John A. Palmer ranche situated at the foot of Palmer Lake between the Hamilton Ranche and the Ranche formerly occupied by Wm. Claussey and adjoining the James Palmer Ranche…” as conveyed from James Kinslow [Kinchelo] to Charles Long by a Quit Claim Deed dated January 5, 1893 and duly noted by Okanogan County, attesting to payment as represented by the sum of One Dollar lawful U.S. money. This deed doesn’t mention the total acreage as does the Case-Smith document. Both deeds transferring “ownership” of these ranchlands rely solely on community cooperation as to the actual land boundaries. Without an eyewitness in 1893, and without an official land survey with distinct coordinates, ownership was at best a questionable concept made even more problematical by the fact that there was no legal ownership of United States government property yet available.

Miners leaving the British Columbia goldfields were drifting into the westernmost section of Stevens County during the 1870’s and early 1880’s in ever-increasing numbers. They soon complained loudly about their inability to secure their investments—labor and a pick-axe–with ownership of the land set aside for the Moses-Columbia Reservation. In response to this loud chorus of disapproval, a fifteen-mile strip—roughly from the International Border to the mining camp at Loomis — was removed from the reservation in 1883, permitting a certain apriori claim to property that would later be eligible for legal ownership under the Homestead Act of 1862. The key provisions of that Act for purposes of land ownership at Palmer Lake at the time are clearly stated: [I’m not making this up] “a person is eligible for a homestead]… who has filed a preemption claim…in conformity to the legal subdivisions of the public lands, and after the same shall have been surveyed.” Ah, there’s the rub.

The U.S. surveys had not reached the Palmer Lake Townships 39 and 40, Range 25 East in 1893. What is more, the 1896 surveys [as partially depicted in our map shown above] were not certified—made “legal” as required by the Homestead Act provision cited above until 1898. Thus, a legal document by Bill of Sale or Deed did not constitute ownership. If a claimer was still on the land when the surveys made filing a preemption claim possible, after a period of five years of continuous occupancy the ownership was secure. It is easy to see the gigantic loophole available to those looking at what may have been their last possible opportunity for land in what has been termed “The Late Frontier”, holding onto, well—for dear life, whatever seemingly empty acres they could find. In the late 1880’s, Fifteen-Mile Strip might just as well have been known as “Last Chance Gulch”—with an abundance of grass, water, space, grazing potential, and empty of much competition. So far.

Where do these indisputable conditions leave George H. Smith and Charles E. Long? In court. During the summer of 1893, Smith filed a complaint against James Kenslow and, on the same day, August 14th, with the same attorney, Michael Kelley filed a complaint against Charles Long. Both complaints cite “claim jumping” by the defendants. The attorney’s handwritten court records do not furnish much information; frontier justice with a circuit-riding judge, apparently did not have much use for faithful transcripts of testimony in cases unlikely to ever be appealed to a higher court. Without citing any legal claim, Smith accuses Kenslow [aka James Kinchelo] of taking possession on January 12, 1893 of the premises, described exactly as noted in the original Deed, during Smith’s temporary absence and thereafter holding it, wrongfully, by force. Smith also alleged that Kenslow tore down and destroyed his cabin, “reasonably worth two hundred dollars” and dwelling house. On October 16, 1893 Judge Wallace Mount declared for the defendant and upheld same on December 20, 1893. Smith appealed the verdict to the State Supreme Court where the case was dismissed.

Michael Kelly complaint attested that the property formerly occupied by the plaintiff, now occupied by the defendant, [consisted of] land “beginning about one-half mile north of Palmer Lake, thence north one-half mile and one-half mile wide, all in Okanogan County…” valued at Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars and included “One Hundred Fifty Tons of wild hay grown, cut, and harvested”; Kelly further claimed that Long unlawfully entered into possession on January 12, 1893 and, adding personal property theft charges, “wrongfully [took] the hay which was then and there growing and being…” In Kelly’s case file, we have the verdict of Judge Mount of October 12, 1893 in Michael Kelly’s favor, restoring the land to his possession and so ordering the Sheriff to so carry out. This decision was also upheld on December 20, 1893.

It is worth noting that Michael Kelly was a Civil War veteran, a status that often gained preference in land disputes (providing, of course, they weren’t Confederate veterans ineligible for homesteads). Impeccable patriotic service undoubtedly worked against Charley Long’s reputation as a trouble-maker at best, a lawless hot-head in general. George H. Smith and Kelly seem to have been friends, judging from their simultaneous lawsuits with the same attorney. It is clear, nonetheless, that whatever legal troubles Smith had, they were not with Long.

It is also clear that James Kenslow, known as Jimmy Kinchelo, had a big problem with both Smith and with Long. Charley Long paid Kinchelo an unknown amount of money (the One Dollar of the deed was and is a common legal minimum) for a ranch. On December 21, 1893, Kinchelo has a more-or-less legal, court-decreed possession of any ranch land he deems is his, some part of which Charley Long may well have figured he bought, paid for, and was entitled to. It is hard to imagine that Charley Long just shrugged and with an “Oh, Well”, walked away from the whole affair. Smith was obviously still residing on the property he lost to Kinchelo—the site of the killing—but challenging Smith wasn’t going to help Charley’s case or to gain possession. If Kinchelo and Long invaded the Smith & Kelly premises on the same day in January 1893 as contended in both court complaints, there remains some suspicion about any agreements they made between themselves as to the next course of action. It may not have been Charley’s reputation that so frightened The Okanogan Kid; Smith may not have been the intended victim, but we know he was armed and prepared for a gunfight, not for a shouting match of intimidation.

Nine men were involved in the struggle for the former Palmer and Case ranchland or had money in the game: The Smith Brothers’ George F. and Jefferson, George H. Smith, and Horace Smith. Jasper Cox of Walla Walla counts as a fifth investor, having bought land from Horace Smith; Michael Kelly (who may have purchased his land claim—no legal documents were filed.); Jimmy Kinchelo and Jack Long, mentioned in the coroner’s hearing testimony; Charley Long is, of course, Investor Number Nine.

Two years later, George F. Smith was convicted of cattle rustling of one (1) cow on the “his” ranch, purchased from Phillips. Smith, Sr. was sentenced to prison for 18 months, served three months before being pardoned by the Washington Governor. It is unknown whether The Okanogan Kid skedaddled, leaving his nickname behind with the land and returning to Seattle; his father maintained that Junior managed the Smith’s nine meat markets on the coast. A person might wonder why the cattlemen of the area would bring such a frivolous lawsuit to court and rid themselves of their principal buyers. Jasper Cox vanishes from the Okanogan; Michael Kelly died before the surveys were certified.

Together, Kinchelo and Jack Long end up with the disputed ranchland before the surveys were If you look very closely at the northwest corner of Palmer Lake in the map reproduced above, you will see Jimmy Kinchelo’s name as being in possession of the property in 1896. Kinchelo was awarded a homestead patent in 1900 for the same land, forever described as Lots 1-6 (which included the water rights of Palmer Creek outlet, by the way) and the SESW of Sec. 35, T40N, R25E, approximately the land Charley Long bought.

The goal for these nine men was clearly to establish a Possession is 99% of the Law claim on legal sub-divisions of prime cattle-raising territory in order to be in a position to file for homestead status. The Okanogan country was one of the few remaining pockets of available land in the West. As an economic opportunity the Okanogan was not so much overlooked as by-passed in favor of better farm land and transportation to the south. Despite a description of the Sinlahekin watershed made by early-day entrepreneurs as the only prime cattle country north of the Kittitas Valley in eastern Washington (think about it in 1870’s), two cow-killing winters of 1879-80 and 1889-90 in central Washington had nearly wiped out even the prospects of profits on cows, let alone the dry-land farming practices of the Palouse country.

Competition for the Palmer Lake corner of the territory began, as we’ve seen, in the mining claims of the 1880’s. The financial depression of 1893 brought economic collapse to the entire country: The stock market collapsed, banks folded, stores went under; the United States repealed the Silver Act, no longer purchasing silver, eliminating the capital investments in mining; the railroads shut down. No credit, no transportation to market, no profit in digging up silver ore. The effects were soon felt in Loomis, Washington. The future was not secure for the new residents and the land status made it worse.

The struggle over the land had become violent and deadly. Charley Long is only one of the deaths in the area that George H. Noyes, U.S. Land Commissioner, reported to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper in September, 1897, the consequences of what he flat-out called a land war: “Complaint has again been made to the general land office that no inspectors have been sent to look over the surveys of Townships 39 and 40 North Range 25 East. A recent letter from Mr. Noyes of Loomis, Wash. announces that ‘another settler has fallen victim in the dilatory workings of the land office, making the seventh. Peter Coutts was fatally shot on the Similkameen River August 23, 1897’ ”.

It may be interesting to readers to note that in 1905, George H. Noyes, U.S. Land Commissioner, was convicted of embezzlement of funds entrusted to him and belonging to his employers. Noyes was sentenced to three years in the state prison but paroled two months before his term was up. Perhaps the feds objected to the “dilatory” part of his public accusations.

Obviously, Noyes hoped that the Seattle press might have more clout in moving the bureaucracy. Five other murders around Loomis in those years, mysterious as well as confessed, were mentioned in the Loomis newspapers (through clippings and existing issues of the Palmer Mountain Prospector); these are stories for another time.

Desperate hardened men with nothing to lose on the edge of either prosperity or failure. Desperados—the common word for outlaws” comes from the Spanish “desperate”—recklessly grabbing a piece of that pie. The Monster of Palmer Lake waiting. Not even remote, struggling Loomis pioneers with their parties, dances, weddings, funerals, and civic boosterism were without the show-downs over land that makes up so much of the mythology of the Old West. But those fine folks did prevail, as they always do.

Photo by Justin Haug