A couple of years ago, the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association made some noise about reconfiguring its classification system. Everything was supposedly on the table, including the potential scrapping of existing districts, setting up a seeded football playoff system, and/or changing the way students were counted when calculating school enrollment.

There were a few tweaks that survived all the politicking: using freshman through junior classes (rather than sophomores through seniors) and deducting alternative school students (who for the most part are not eligible for interscholastic athletics) when calculating enrollment.

Good changes, but not enough. Persistent issues still exist that require a more thorough rethinking beyond what a slow evolution can accomplish.

The likelihood of this happening is rather slim. What amounts to a reboot of the whole system requires a lot of momentum from a supermajority of the WIAA’s member schools, and getting so many school districts and athletic personnel – all charged with defending the best interests of their own schools’ kids (which doesn’t always fit into the big picture) – to agree on anything so comprehensive is probably impossible, especially considering the athletic, economic and social diversity of the state.

Still, there is a better way to do this. I’ve been around high school sports in multiple states almost constantly for a couple of decades, both as a reporter and as a parent. I’ve talked to uncounted coaches, athletic directors, parents and athletes about issues like competitive balance, travel, and the needs of the 99 percent of high school athletes that won’t be getting athletic scholarships to play in college. Most of that has been just casual conversation, not in “reporter” mode, but over the years it’s shaped my thinking in more ways than even I probably realize.

Bottom line, it’s not about capturing that rare full ride to school, but making interscholastic athletics the most beneficial experience for the athletes, schools and those that support them.

So here’s my stab at it.

Symptoms

Much of what ails the current system has reared its head on several occasions this year, and close to home here in the North Okanogan.

Some examples:

– Oroville’s Central Washington 2B League schedules feature away games that average 148 miles. The football team played at Kittitas (200 miles) last fall; the basketball teams will travel to White Swan (267 miles) in January.

– At least those trips are on weekends. The Oroville volleyball team played a first round district playoff game on a weeknight in White Swan. What should have been a big deal for the school was a non-event for most, as the team had to leave Thursday morning and returned at something like 3 a.m. Friday. Only a handful of parents were able to make the trip. That’s two days of school (physical absence on Thursday, abject fatigue and mental uselessness on Friday) – not for a state tournament experience, but for one match in an opponents’ gym.

– Tonasket’s travel isn’t quite as bad, averaging 84 miles per road trip. The football team played Caribou Trail League road games back-to-back weeks at Cascade (135 miles) and Cashmere (124 miles).

– On top of the distance issue, there are vast differences the socio-economic base of the various schools that affects competitive balance. Drive through Leavenworth, Cashmere and Chelan, and you can see the difference with just a glance. This shows up in the size of athletic budgets and the resources brought to bear by booster clubs, from the necessities of replacing used equipment to the more trivial but visible events like having homecoming royalty delivered at halftime by helicopter.

– Just up the road in the Methow Valley, a deserving Liberty Bell football team was denied a state playoff berth. The Mountain Lions finished tied for second in the CWL with state-qualifying Oroville, who beat Liberty Bell mid-season. The problem: the CWL only had two playoff berths available for seven league teams, while other leagues around the state were afforded berths for half of their squads. Liberty Bell was ranked sixth in the state in the Scoreczar.org computer rankings but didn’t get to prove it in the playoffs.

– The debate never ceases on getting the right teams and athletes to state competition. One of my beefs is what happens to the smaller school events. Girls soccer has a four team 1B/2B tournament. State wrestling includes an eight-man 1B/2B bracket that is virtually ignored (other classifications are 16-man). The cross country 1B/2B field is half the size of the others. Some events at the 1B state track and field finals – which also have just eight spots, rather than 16 – aren’t even filled.

Classification complications

The state classification system, based on enrollment, includes six enrollment groups: 4A, 3A, 2A, 1A, 2B and 1B. Every two years, schools are moved up and down in classification (or left where they are) based on changes in their enrollment. Every four years, the dividing line between classifications is renegotiated, a lengthy process which is currently in its final stages for the next four-year cycle.

Coming up with an equitable system there is a never-ending debate. There are basically two schools of thought: divide the classifications equally by number of schools; or by keeping the number of students of the larger schools proportionate to the number in smaller schools.

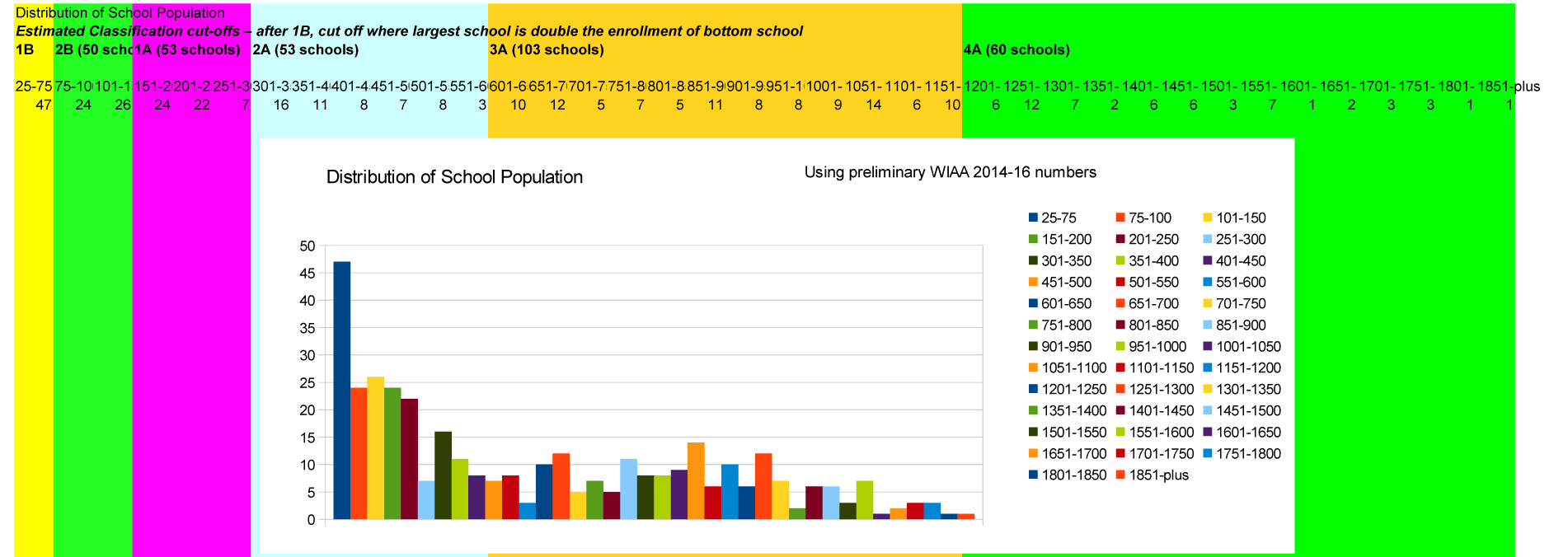

Both philosophies have pitfalls, because in Washington there is not an even distribution of school populations. It’s not something that can be controlled, but the fact is that there about 150 schools with a WIAA enrollment of 250 or less; there are approximately that same number of schools in the 250-1250 student range.

Thus the challenge. If, say, the state divides its schools into six classifications of about 64 schools each, you can get a situation where the largest school in a classification is three times the size of the smallest such school.

If you limit the largest member of a classification to being, say, double the size of the smallest, you can end up with 40 schools in one class and 90 in another. And that matters because schools in more crowded classifications end up with a much more challenging path to qualifying for a state tournament.

And while that’s where a lot of the talk and negotiations have centered in recent months (and won’t be going away any time soon), nearly all the real issues are complicated by the existence of permanent WIAA districts.

Allocation blues

All WIAA member schools are also members of one of nine districts, a map of which looks like any gerrymandered political map.

Both Tonasket and Oroville are part of District 6, which includes all eight Class 1A Caribou Trail League schools. In Class 2B it includes the six northernmost CWL schools and in 1B includes 11 more CWL schools. It also includes five of the six Big 9 3A/4A league schools.

Leagues are formed with like-class schools within their own district, and in some cases combine with another district that may not have a lot of schools in a particular classification (hence District 5’s White Swan and Riverside Christian ending up in the CWL).

Playoff allocations – the number of entries each league is given into the eight or 16-team playoff brackets – are meted out to each district. Or, in some cases, a combination of districts, like 5 and 6 in Class 2B, or Districts 6 and 7 in Class 1A. The Caribou Trail League and the North East A League (District 7) combine into a bi-district to whittle down to state qualifying teams and individuals.

With schools locked into particular districts though, there is no balance in numbers. For instance, District 8 includes only the Greater Spokane League 3A and 4A schools. District 9 has (for most sports) five 2B schools and nine 1B schools. District 7 includes seven 2A, seven 1A, eight 2B and 13 1B schools. District 3 encompasses 10 entire leagues of all classifications.

So, the number of teams that get access to state tournaments from each district must be determined by committee. The results are often inconsistent, such as the situation that kept Liberty Bell out of the state football playoffs.

You also get a different number of allocations from year to year – last year CWL 2B football had three state spots, this year just two. In track and field, for example, you sometimes have three male qualifiers and four female qualifiers for the same event, or different numbers of qualifiers for sprints and distance events. A neighboring district, depending on how many schools it has in that classification, might have only one or two … or both.

From year to year it is difficult to know what to expect, and sometimes the allocation numbers aren’t even determined until halfway into the season. There is a lack of consistency from district to district, season to season and sport to sport.

Another example: track and field allocations, which you can check out here at the WIAA site.

Districts also each have their own rules to determine their state qualifiers. In girls soccer last fall, the CTL determined that its top four teams would advance to a Bi-District playoff with District 7, with its fifth and sixth-place teams playing to determine a fifth entry. However, District 7 had a full four-team district playoff to determine which three teams to send to the Bi-District.

Dumping the districts

The districts and allocation system represent artificial barriers to setting up geographically appropriate leagues, as well as to keeping the playoff system consistent and predictable.

In my benevolent dictatorship, the districts as permanent entities wouldn’t exist. And the 4A/3A/2A classification system would be in play only for sports in which the vast majority of schools in all classes participate.

Without the districts, the current allocation system disappears and leagues can be formed as they so choose in the absence of artificial barriers … and even across classifications, if so desired.

There are a few of those leagues already – the Northwest Conference ranges from 1A to 3A, for example – but this just adds to an already convoluted playoff qualification set-up.

But in this remake, allocations and class-specific leagues aren’t needed because everyone gets into the playoffs. Yes, even the woebegone 0-20 basketball team (football is the exception to the rule, which we’ll deal with later).

Regular season

State playoffs and meets are the goal of just about every team and individual, and in most sports districts and regionals are the path to get there. But most blood, sweat and tears are shed during those 10 or so weeks of the regular season.

One thing some small school leagues in the eastern part of the state lack that the larger westside leagues have are true intracounty rivalries. The leagues are so spread out, and most fans other than the most devoted parents aren’t going to make 4-6 hour road trips throughout the season.

Many leagues might stay as they are if given the choice. But for the sake of argument, let’s look at the possibility of a county or regional league in our part of the state.

This currently-fictional NCW league could consist of schools such as Bridgeport, Brewster, Lake Roosevelt, Liberty Bell, Manson (given history and a lack of a better option), Okanogan, Omak, Oroville and Tonasket – all 2B and 1A schools – and perhaps even include borderline 1B schools like Pateros, Entiat and Waterville in non-football sports.

The idea is to keep it local and keep it competitive.

With that many schools, splitting into divisions is almost a necessity – north and south, big school and small school, whichever. The goal of playing for a league championship remains the same as it’s always been. It just doesn’t affect post-season play.

Competitively, there would be the cyclical ups and downs as there have always been.

Financially, it would be a big boost to just about everyone involved.

Even with Waterville and Entiat involved, Oroville’s average road trip for league games would drop from its current 147 miles down to 71 – less than half. Other CWL teams would see similar reduction in travel: Liberty Bell (118 miles per trip to 58); Bridgeport (97 to 41); Manson (97 to 54); Lake Roosevelt (109 to 65).

There’s big drops in travel for the north end CTL teams that might move to a more compact league: Tonasket (84 miles per trip to 57); Omak (64 to 41); Okanogan (61 to 39); Brewster (55 to 37).

Transportation costs go down; with shorter transportation times, kids miss less time in class; and with more road games closer to home, it’s likely gate receipts improve.

A lot more visiting fans (and maybe even home fans) will attend an Oroville-Tonasket league game than Oroville vs. White Swan or Tonasket vs. Cascade.

Without artificial district barriers, a school like Republic could be included in such a league. Or Brewster, as it has historically done, may seek out tougher competition and head south to join with larger schools. Or decide to play as an independent, which creates all sorts of headaches in the current system but wouldn’t have post-season implications in the Half-baked version of the WIAA.

Part 2 next week will examine various scenarios for post-season play, from districts to regionals to state, in team and individual sports.